Indigenous people from the Madija Kulina, Kanamari and Deni ethnicities together form 5 Indigenous Lands, of which 3 still call for demarcation and protection

By Raimundo Francisco Silva (Manuel) and Nathália Messina, reviewed in Brazilian Portuguese by Cristabell López

Translated by Bruna Favaro

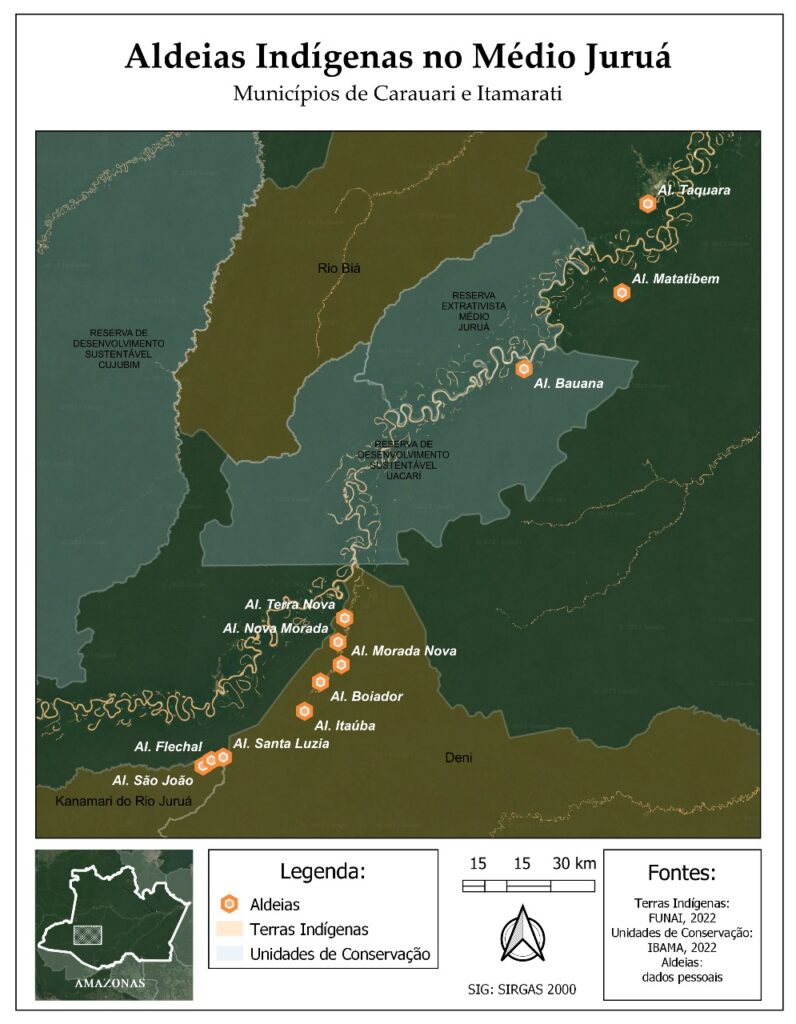

In the depths of the Amazon, where the Juruá River meets the living and thriving forest, a cultural wealth resides and endures over time. In the middle portion of this river, commonly called the Mid-Juruá Territory, in the boundaries between Carauari and Itamarati, we observe the ancestral presence of the Madija Kulina, Kanamari and Deni indigenous peoples.

These people are distributed across the territory in 12 villages and 5 Indigenous Lands (IL), of which 2 are demarcated and approved – which are the IL Deni of Xeruã River (with five villages) and the IL Kanamari of Juruá (with three villages and a new formation) – both located in the municipality of Itamarati, that has a population of 1617 indigenous people, according to data from SESAI (Indigenous Health Secretariat) from 2023. Another 3 ILs, with one village in each, are in the process of claiming. These are: the IL Kanamari of Taquara, IL Kanamari of Bauana and IL Kulina of Uerê, all located in Carauari, whose indigenous population is estimated at 509 people (Sesai, 2023). Among the indigenous lands of Carauari, land of the Kulina people of the Uerê River has its demarcation process at an advanced stage, just awaiting the land survey and its approval, which will make it possible to guarantee a safe and dignified future for next generations.

Juruá, in a demonstration for the improvement of SESAI in 2019.

Historically, indigenous peoples have suffered from the most diverse types of violence and rights violations. Over time, peoples in the region were forced to migrate from their territories to get away from the non-indigenous population. During the rubber cycle period – with the rubber plantations and the settlements of rubber tappers – there were many conflicts that led the indigenous peoples to distance themselves from this context of oppression. Contacts, by default, were always violent and had several consequences between peoples, such as the transmission of diseases, like the measles epidemic that attacked the Deni and resulted in many deaths due to low or lack of immunity and treatment. With the end of the rubber cycle and the arrival of the Catholic church and the priests who made the first contacts with the peoples of the region, COMIN (Council of Missions among Indigenous Peoples) established a friendly relationship, seeking to bring support and development bodies – such as FUNAI (National Foundation of Indigenous Peoples) and other collaborators – in order to defend the rights and well-being of these peoples.

Subsequently, CIMI (Indigenist Missionary Council) entered the scene, offering health and educational services to indigenous peoples, including teaching the Portuguese language and aspects of legislation, so that they could begin to see themselves as subjects of rights. In the history of struggles and social movements in the region, the participation of OPAN (Operation Native Amazon) also deserves to be highlighted. The project acts in Mid-Juruá, providing support to some of these peoples and also has played a significant role in the land demarcation process. In the case of IL Deni, CIMI, OPAN and Greenpeace joined forces in 2002 and, in 2003, carried out self-demarcation to guarantee the approval of the territory, which took place in 2004, and then took action to protect these lands once threatened by interests of WTK, a Malaysian logging company, which presented a title for exploration. These demands were consolidated and provided protection, paving the way for the arrival of public policies in the villages, such as education and health, with the presence of SESAI. Although there is much to be done, significant progress has already been achieved by the Deni.

festivities in 2023.

in Boiador Village, Deni IT, in 2022.

Through all of this, we emphasize the importance of cultivating solid and prospective partnerships to strengthen their causes and the indigenous peoples, who, over the years and still today, are proven to be the main responsible for creating, managing and maintaining the living forest. Thus, Instituto Juruá, in partnership with indigenous-based organizations and indigenous institutions, consolidated in the territory, has been seeking to establish greater contact and dialogue so that collaborative solutions, led by indigenous peoples, bring positive results, resilience and hope for a present and a future that guarantee the life and cultural safeguard of these ancestral lands.